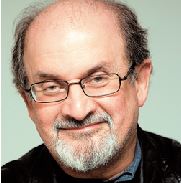

Το εξωτικό στοιχείο και η καλή γνώση του αντικειμένου για το οποίο γράφει ο συγγραφέας είναι δύο από τα κλειδιά για το βραβείο Μπούκερ, σύμφωνα με τον Μάρτιν Γκοφ, που διοργάνωνε τα βραβεία επί 35 χρόνια. «Ο λογοτεχνικός τουρισμός παίζει σημαντικό ρόλο. Δηλαδή η ικανότητα του συγγραφέα να μεταφέρει τον αναγνώστη σε ένα μέρος όπου δεν έχει ξαναπάει. Φυσικά, ρόλο παίζει και μια καλή υπόθεση. Αλλά θα πρέπει να συνοδεύεται από μία περιγραφή όσων δεν ξέρουμε. Πάρτε για παράδειγμα τον Σάλμαν Ρούσντι και την Ινδία. Ο κόσμος γοητεύεται από κάτι τέτοιο». Αυτές τις μέρες θα ανακοινωθεί ποιος από τους έξι υποψήφιους συγγραφείς θα πάρει το φετινό Μπούκερ. Ο Ρούσντι πήρε ήδη για το βιβλίο «Τα παιδιά του μεσονυκτίου» (στα ελληνικά Εκδ. Ψυχογιός) το Μπούκερ το 1981 και χτες σε ψηφοφορία για τα καλύτερα των βραβείων Μπούκερ πήρε και το Βest of the Βookers. Τα τελευταία χρόνια όμως, το βραβείο φαίνεται να έχει αποκτήσει πολύ μεγαλύτερη βαρύτητα από ό,τι παλιότερα, κάτι που δεν εγκρίνει ο Γκοφ. «Τα πρώτα χρόνια οι συγγραφείς ήθελαν απλά να γράψουν ένα καλό μυθιστόρημα. Τώρα, σκοπός τους είναι να γράψουν ένα μυθιστόρημα για να κερδίσουν το Μπούκερ». [ΤΑ ΝΕΑ, 11/07/2008]

From The Times, July 10, 2008

Victoria Glendinning, chair of the shortlist committee, asks 'what makes a novel an enduring classic?'

The people have spoken. It's Midnight's Children!

The Best of the Booker, celebrating forty years of the prize, was a big, simple idea. We three who chose the shortlist did not pick the winner. You the readers did, voting in your thousands. It has turned out to be much more interesting than a mere marketing exercise - not that any exercise for marketing major novels is “mere”. Criticism of the Booker, or Man Booker as it is now, has often centred on the choice of judges. They did not always seem to reflect the prize's true constituency - the readers. That is why Best of the Booker is unique.

When we began studying the list of forty-one winners, from 1969 to 2007, I realized I was reviewing my whole novel-reading life. For my fellow judges Mariella Frostrup and John Mullan, who are not as old as I am, the early part of the list was historical. But for all of us there was an unavoidably autobiographical strand in our responses. William Boyd, himself a short-listed Booker author, expressed this perfectly in the introduction he wrote to Alasdair Gray's Lanark: “It may not be immediately apparent at the time of reading, but the person you were when you read the book, your state of mind while you read it, your personal situation (happy, frustrated, depressed, bored) and so on - all these factors, and others, make the simple experience of reading a book a far more complex and multi-layered affair than might be thought. Moreover, the reading of a memorable book somehow insinuates itself into the tangled skein of personal history that is the reader's autobiography: the book leaves a mark on that page of your life - leaves a trace - one way or another.”

It follows that the three of us were not in instant agreement. Not at all. For each one of us, a personally significant book had to be axed from the final shortlist because the other two judges were not in sympathy. This was painful. Some novels, which had seemed irresistible when first published, now seemed to one or more of us quite weak. This was disturbing. It was either because they were essentially backward-looking - a particularly good example of something readers were used to, at that particular time - or, at the other extreme, because they were so utterly of and for their moment that, like a fashion in clothes, they dated. A more difficult category consisted of winning novels by writers we all admired unreservedly, who would include V.S.Naipaul and Margaret Atwood, but felt that the prize had been given for the wrong book. We were assessing individual works, not lifetime achievement.

The voters have not, of course, chosen the definitively best novel from Britain, Ireland and the Commonwealth written in the last forty years. There is no such thing. Another panel would have come up with another shortlist. Our choices were determined by the list of previous winners, who had in turn been rewarded by the idiosyncrasies of judges in any given year. It's all a bit fortuitous.

Yet the lists tell their own story. So many gifted novelists over the past forty years have written about the two world wars and the end of empire, as if a more truthful perspective, and the need to explore and understand these cataclysmic events through individual stories, had become urgent for both writers and readers. Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children (1981) is a “hinge-novel”, in form, in content and in orientation, and that is I believe why it has won. No longer would fiction about India or Africa be written through the lens of the imperial sensibility, in the tradition laid down by Orwell, Forster, and Paul Scott. And there will doubtless soon be another hinge-novel, to transform our perceptions again, about something completely different.

Exhilarated by so much that was visionary, eccentric, wide-ranging, we were unable to include any of the quieter novels focussing on private life, which we regret. We did not think about gender or ethnicity; our only test was whether a Booker winner, whenever it was written, spoke strongly to us today, stretching our imaginations and the resources of the English language. That is perhaps the beginning of a definition of a classic.

The Best of the Booker shortlist:Pat Barker's The Ghost Road (1995), Peter Carey's Oscar and Lucinda (1988), J.M. Coetzee's Disgrace (1999), J.G. Farrell's The Siege of Krishnapur (1973), Nadine Gordimer's The Conservationist (1974), Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children (1981)

No comments:

Post a Comment