The world was rocked by terrorism, climate change became an emergency, celebrity culture moved from our TVs to our bookshelves, and a boy wizard held millions spellbound. Love them or hate them, these are the 50 books that defined the decade

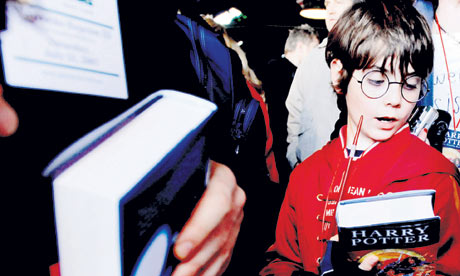

Fans receive their copies of 'Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows', July 2007. Photograph: TRACEY NEARMY/EPA

2000

Julian Barnes on White Teeth, by Zadie Smith (Penguin)

When I began to read White Teeth (as a judge for the Guardian First Book award) my preponderant feeling was one of relief. Relief that, despite the loudest hype for a first novel in my lifetime, the book itself was very good. Relief that its author, despite ticking all the boxes of promotability, was a serious writer. Relief that, despite being touted as "the multicultural novel for our time", it also spread more widely, and was as much about religion and faith as about race. Relief, too, that as a novel it was far from perfect – which might have been unbearable – and accorded to someone's definition of the novel as "a long piece of prose with something wrong with it". Even at the level of surface fact, there are numerous errors, especially in the war section (where tanks suddenly turn into jeeps and pistol bullets produce shrapnel).

The almost preposterous talent was clear from the first pages. You can't teach a writer ear: White Teeth is a feast of aurality, of overlapping, interweaving, interbreeding modes of speech. You can't teach a writer eye, or curiosity about what they aren't interested in: Smith's appetite for subject-matter is gluttonous. You can't teach a writer tone of voice: Smith's is tremendously assured, controlling, veering towards the bossy – though also at times yielding to the first novelist's nervous weakness for putting in stuff just so that the reader will not be in any doubt that he or she knows stuff.

What the novel gives off, with and beyond all this, is the sheer excitement of literary creation. Most practitioners of the arts have moments when they doomily, self-pityingly feel that the form they work in is about to collapse: because of rival technologies, consumer apathy or lack of interest from the next generation. So Smith's traditionalism – her implicit belief that prose fiction is still the best way of describing and understanding the world – was perhaps the greatest relief.

Cheek is also a useful attribute of the first novelist. One page of White Teeth that I especially enjoyed contains a long, rich riff on school smoking habits. All the cool kids favour dope, or at least something of an illegal nature, whereas the school's dullards gather in nerd-herds to share boringly legal cigarettes. The typical fag smoker, according to this page, is "a little featureless squib called Mart, Jules, Ian". When introduced to the author at the award ceremony, I sternly informed her – speaking for the other two as well – that this page had not escaped our attention, and that "we" would be keeping our eye on her. We have been ever since, with continuing admiration. •

✒ No Logo, by Naomi Klein (Fourth Estate)

Bestselling exposé of the nefarious activities of Nike, Shell and other corporations, which became an inspiration for the anti-globalisation movement.

✒ The Tipping Point, by Malcolm Gladwell (Little, Brown)

First book from the pop sociology phenomenon, which seeks to explain why small changes can have a big impact on social trends.

✒ A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, by Dave Eggers (Picador)

A heartbreaking account of his parents' deaths from cancer, with footnotes and tricks. Gave the misery memoir literary credibility.

✒ The Amber Spyglass, by Philip Pullman (Scholastic)

Final part of the magisterial Northern Lights trilogy, which created its own mythology while setting new standards in crossover fiction.

✒ How to Be a Domestic Goddess: Baking and the Art of Comfort Cooking, by Nigella Lawson (Chatto & Windus)

Kickstarted the cupcake revolution and became the bible for the yummy-mummy generation.

✒ Experience, by Martin Amis (Vintage)

The messiness of a life backlit by celebrity is poignantly detailed in a scrupulous and candid memoir by a writer incapable of writing a dull sentence.

2001

Joshua Ferris on The Corrections, by Jonathan Franzen (Harper Perennial)

It was the book you had to read. And by "you" I mean not just you, writer of fiction, follower of literary trends; I mean also your father-in-law, your little sister. If you were an American, certainly, or for that matter any citizen of a first-world, late-capitalist nation, The Corrections had your number. How often does the spectrum of praise run from Pat Conroy to David Foster Wallace? It was a phenomenon that seemed to come out of nowhere. Franzen had written two previous novels, but in 10 years only a few provocative essays, and nothing to indicate that here would be the writer to tell us – if every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way – how the American family was unhappy.

Which is not to suggest the book was bleak. It was merciless, it was skewering, the family at its heart full of bicker, betrayal, and many other varieties of familial sport – but the artist assembling and synthesising it all for the pleasure of the reader was possessed, thank God, of a voracious emotional intelligence, capable of mollifying all that was ugly and unlikable in his individual characters with empathy and humour. Oh, it's compulsive reading! The copy I have is a hardback containing 568 pages, and not one of them flags. The sentences are rollicking flickers of genius, one brilliant-dense paragraph meeting another, narratives vectoring into the outlandish and the unexpected while remaining ever committed to the realist's agenda. We might have forgotten, by the time the book landed, that a literary doorstopper of the first order of seriousness could also be unabashed entertainment. More likely Franzen simply knew that all comedy is deadly serious, and that the fraudulent online sale of post-Soviet Lithuania, for example, or a stolen salmon fillet sliding down the hero's underpants, was the low-brow fallout, the comic carryover, of a writer dividing the sadness of a declining family by the sadness of a declining culture. The book was a howl: against greed, against selfishness, against the axiom of American happiness, finally against the tyranny of family holidays.

It stirred a specious controversy when Franzen, possessed of so fine a sense of ambivalence towards the commercial ends of things that he could write a book like The Corrections in the first place, was caught discomfited by the book's popular embrace. But now that dust-up seems squarely of its time and place, while the book has achieved timelessness. Told in the expansive tradition of Dickens and Tolstoy, fluent, uncompromising, accessible, expressive of an awesome amount of contemporary experience that remains all too familiar today, The Corrections continues to be the exemplary novel of postwar American family life. •

✒ Atonement, by Ian McEwan (Jonathan Cape)

Second world war country-house love story indebted to The Go-Between that made McEwan a household name.

✒ Austerlitz, by WG Sebald (Penguin)

Melancholy, genre-bending novel of a 20th-century Jewish life from one of the decade's most admired writers.

✒ A Life's Work: On Becoming a Mother, by Rachel Cusk (Fourth Estate)

The first and most uncompromising example of the new focus on motherhood.

2002

Polly Toynbee on Nickel and Dimed: Undercover in Low-Wage USA, by Barbara Ehrenreich (Granta)

Images of brutalising work will linger a lifetime for all who read Barbara Ehrenreich's journey through the circles of low-wage hell. She lifts the carpet to look at the humanity working beneath the shiny public face of the United States. Read this and you will forever find yourself asking who is cleaning your hotel room. Is that smiling Have-a-Nice-Day waitress living in a homeless shelter? In that bright nursing home, is one exhausted care assistant all alone on a double shift with a room full of demented old people? Has that Walmart sales assistant had nothing to eat all day but a packet of Doritos?

Here, on $7 an hour, are America's working poor – too poor to rent a flat or even a room, sharing run-down motel rooms and mobile homes on the far outskirts of cities where buses hardly run. They do essential work in the unseen services that oil the wheels of society. These jobs can't be globalised: no one's granny can be bathed in Lahore. No one's office can be cleaned from a call centre in the Philippines. This is work that must be done by someone, cleaning, caring, catering or at the checkout, unnoticed hands toiling beyond exhaustion, without healthcare if they fall sick. Their daily existence is as perilous as any Dickens described.

Ehrenreich is one of the great American reporters. Taking on these jobs herself across the States, her hawk's eye for detail swoops down on the petty tyrannies of martinet supervisors and the bullying contempt that accompanies contemptuous pay rates. She has an intellectual depth of analysis on this malfunctioning economy that Orwell never attempted in Down and Out in Paris and London or The Road to Wigan Pier. She explores the great failure in the market forces still celebrated by classical economists cleaving to notions that Adam Smith's invisible hand of the market will always produce the best of all possible worlds, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

In many US cities there is a shortage of people to do these jobs, as property developers take over anywhere cleaners, carers or cashiers can afford to live. In Minnesota labour is scarce, so why don't wages rise? Because the market doesn't work like that for the low-paid. Cartel group-think sees hotels, restaurants and office cleaning companies conspire to keep local wages low and suffer staff shortages, rather than compete for labour and all pay more.

The Maids is a cleaning company keeping up appearances in suburban executive homes. Ehrenreich and her crew speed-clean with only a regulation half bucket of dirty water – no time to change it – sprinting from house to house all day, wearing on their backs a vacuum-cleaner pack the weight of a heavy machine gun. The life-support systems of the affluent rely on crippling this army of underpaid starvelings. British readers will recognise the syndrome and its economic dysfunctions – but for us it is also a timely reminder of the life-saving value of a welfare state where at least housing benefit pays the rent, tax credits pay for children and the NHS is free. •

✒ London Orbital: A Year Walking Around the M25, by Iain Sinclair (Penguin)

High-strung account of circumnavigating the metropolis from the phrase-making guru of psychogeography.

✒ Fingersmith, by Sarah Waters (Virago)

Raising historical fiction, lesbian characters and mystery plotting up to the literary high ground.

✒ Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood and the Story of a Return, by Marjane Satrapi (Jonathan Cape)

The Iranian revolution in comic strip.

2003

Mark Lawson on The Da Vinci Code, by Dan Brown (Corgi)

It's a tempting metaphor for literary pessimists that, in 1968, John Updike appeared on the cover of Time magazine, while, four decades later, the bestselling novelist given this symbolic accolade was Dan Brown. If, as many American writers and critics now claim, serious writing is dead, then it's Brown who must be taken down to the station for questioning. He somehow convinced almost 90 million people around the world to read a book which has an opening sentence that sounds like scribbled notes for a screenplay – "Renowned curator Jacques Saunière staggered through the vaulted archway of the museum's Grand Gallery" – and then becomes progressively less literate.

So how did the writer of three little-noticed thrillers become, with his fourth book, the only novelist in the 21st century to challenge the sales of JK Rowling's seven-volume Potter sequence? The most obvious explanation is that this story of a conspiracy lasting two millennia – the Catholic church's brutal and cunning cover-up of the fact that Jesus and Mary Magdalene had children – chimed with a time of paranoid suspicion about official institutions and religions, as the American government fought a war against terrorism in which both sides were led by those of strong religious faith.

There's surely also a clue to Brown's success in two other literary genres that have flourished during this decade. This was a period in which factual books containing arcane information – biographies of 15th-century mathematicians and the Do Wasps Have Prostates? school of popular science – jostled novels off the bookshop shelves, creating a readership likely to be drawn to fiction which tells you things.

It's also likely that many of those who were given the volume as a gift – what a boon for birthdays and Christmas finally to have a book suitable for those who don't read! – will also have been given copies of sudoku or other brainteaser books, another publishing phenomenon of the Noughties. Regular fiction readers find it implausible that dying people, serial killers and architects can be bothered to hide Fibonacci numbers on their walls or their bodies; once-a-year fiction-tasters may find it reassuringly non-literary.

The book brought Brown the life that tends to come with a global readership now: living reclusively in a mansion, hiding from plagiarism suits and weird communications from readers. The Da Vinci Code was a slow-burner, reaching peak sales a couple of years after publication, but it was followed in 2009 by a fast-blazer: The Lost Symbol, reputed to have the biggest initial print-run in fiction history. It was more or less the same book again, with his symbologist discovering that the founding fathers of the USA had turned Washington into a crossword puzzle which a sinister cult didn't want solved 200 years later. But why shouldn't Brown write The Da Vinci Code again when so many other authors had? His legacy has been shelves of opportunistic thrillers with titles like The Galileo Codex and The Michelangelo Matrix.

The only consolation from John Updike's death in January 2009 was that he missed the latest book and film (Angels and Demons) from his degenerated successor as Time frontman. Is this what fiction in the 21st century has become? A novel by someone who doesn't know how to write for people who don't much like reading? •

✒ Landing Light, by Don Paterson (Faber)

All early promise confirmed in a collection that saw Paterson elevated to the front rank of contemporary poets.

✒ The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, by Mark Haddon (Vintage)

Crossover novel about autism and family breakdown that didn't censor itself for children or infantilise adult readers.

✒ The Kite Runner, by Khaled Hosseini (Bloomsbury)

The novel that made Afghanistan the talking-point of every book group.

✒ Eats, Shoots & Leaves, by Lynne Truss (Profile)

Pedant's revolt against bad grammar that became the ultimate posh loo book.

2004

Jonathan Freedland on The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States (WW Norton)

There are few more wounding insults in the literary arsenal than the one that says "written by committee". We know what such books are like: bland, diluted where they should be strong, stodgy where they should be lean. Those keen to pile on the insults might further damn a book by saying it "reads like a government report". Translation: mind-sappingly boring.

How odd, then, that one of the most critically acclaimed and bestselling books of the century's first decade was a government report written by committee. The 9/11 Commission Report had everything against it. Instead of a single authorial voice, it is credited to the 10 members of the commission and their staff of 80. What's more, those 10 commissioners were all former politicians, chosen on strict partisan lines: five Democrats, five Republicans. (At least the current Chilcot inquiry into Iraq includes two published historians.) Less propitious still, the report was timed to appear in time for the 2004 presidential election. Surely it would be both rushed and timid, fearful of offering any conclusions that could help one side over the other. To cap it all, the commission's chairman, the former New Jersey governor Tom Kean, was set on delivering a unanimous verdict, which had to mean firm judgments would be driven out by fudge and that sharp sentences would make way for windy, convoluted ones.

All those preconceptions were blown away more or less at once on 22 July 2004 – the day the report was handed to President Bush and put on commercial sale in bookstores around the US. Sceptics only had to read the first sentence to know they were not holding any ordinary government report: "Tuesday, September 11, 2001, dawned temperate and nearly cloudless in the eastern United States. Millions of men and women readied themselves for work."

The first, narrative section of the report continued in that vein, telling the story of 9/11 as if it were the darkest of political thrillers. There were cuts between locations, cliffhangers to end chapters, a sinister villain brooding in the shadows. It was less royal commission, more 24. Except in this story, there were no good guys to save the day.

The book shot to the top of the New York Times bestsellers' list and was nominated for the National Book award for non-fiction. Reviewers praised the restraint of the prose. "The dominant tone is wise and sad, not angry," said the Washington Post. "Rhetorically, the knowing shake of the head trumps the angry clench of the fist." One review noted the similarity of the language – spare and bare – to that of the "misery memoir". The report was written, it said, in the "language of American pain".

The commission's recommendations may well not survive close scrutiny in the decades to come. Several experts believed the commissioners fell foul of the very error that afflicted the intelligence agencies before 9/11: they were able to imagine only what had already happened, and so could not advise America on how to protect itself from a danger as yet unknown and with no precedent. But even if The 9/11 Commission Report does not endure as a policy statement, it may well live on as a narrative account of the defining event of the early 21st century. As Kean said at the time: "I wanted this to be a document that, 100 years from now, when some child wanted to know about 9/11, they're going to pull this off the library shelf and be able to read it." On that measure, he surely succeeded. •

✒ Small Island, by Andrea Levy (Headline)

An affectionate and historically important portrayal of the struggles of the Windrush generation that won the Orange prize.

✒ The Line of Beauty, by Alan Hollinghurst (Picador)

Booker-prizewinning story of a gay Oxford graduate who navigates the hedonism and hard-heartedness of the Thatcher era.

✒ Cloud Atlas, by David Mitchell (Sceptre)

Global-ranging, genre-busting novel in six parts that made Mitchell a cult hit.

✒ Being Jordan, by Katie Price (John Blake Publishing)

The queen of the celebrity memoir – Price's novel Crystal outsold the entire Booker shortlist in 2007.

✒ Earth: An Intimate History, by Richard Fortey (Vintage)

Literary consolidation of the revolution in earth sciences that began in 1965, chronicling an astonishing shift in how we see the world.

2005

Vince Cable on Freakonomics, by Steven D Levitt & Stephen J Dubner (Penguin)

Like a lot of people who studied economics and call themselves economists, I often feel frustrated with my own subject. I didn't embark on economics to become an applied mathematician or model builder. I wanted to understand how the world around me worked; why people behave the way they do. Traditional economics has helped to answer a few interesting and important questions, such as why and how countries trade with each other, why prices go up and down and why we get inflation or unemployment. But most aspects of human behaviour have remained unexplained or have fallen into the domain of social anthropology or psychology.

Steven Levitt has changed social science fundamentally by opening up a wide range of social and individual behaviour to economic analysis. His key tool is understanding incentives. Economists have traditionally seen incentives in terms of price (or price as a trade-off against leisure or risk aversion or other components of a utility function). Levitt looks at all aspects of behaviour and tries to understand the individual motivation that drives it. Another tool is the use of information: who has it and how they use it. Freakonomics provides a wide range of problems which it is possible to solve using these tools. And others – such as Tim Harford, the FT's "Undercover Economist" – have added to the richness of this new approach.

Levitt's best-known insight arises from his attempts to explain crime, and in particular the remarkable decline in violent crime in the US in the 1990s. He examines all the popular explanations – more capital punishment, longer prison sentences, economic growth, stronger gun-control laws and better policing. He finds that, while each hypothesis may be superficially plausible and go some way to explaining a small part of the change, the evidence suggests that there is another, deeper explanation: the legalisation of abortion following Roe v Wade.

Following this ruling, large numbers of unwanted children were no longer born to poor mothers in neighbourhoods with the highest incidence of violent crime. Levitt's hypothesis was tested with positive results over time and across states (and internationally). He makes no moral or political judgment on abortion, but identifies from evidence a key set of motives and incentives: the positive commitment (or not) of a woman to having children and raising them well.

A lot of Levitt's work satisfies his own intellectual curiosity but isn't of any practical value. But the work that is of practical value is often counterintuitive and shocking, and all the more valuable for that. He establishes that home swimming pools are more dangerous than handguns, for example. His most interesting work involves explaining cheating behaviour, corruption, criminality, especially with drugs. Here there are many myths and prejudices, and Levitt forces us to consider evidence, not preconceived doctrine, as a basis for policy.

Much of his work ventures very far from what we normally call economics and for that reason may produce a sniffy reaction from the professionals (and those from other disciplines who may fear a territorial raid). But as the introduction acknowledges, Levitt is returning economics to its roots, in particular to Adam Smith. Smith's two great books, The Wealth of Nations and The Theory of Moral Sentiments, tried 250 years ago, using objective evidence, to understand the links between individual motives and the working of society. Levitt helps return our discipline to its proper purpose. •

✒ Untold Stories, by Alan Bennett (Faber)

Delicately finessed personal revelations ensured we loved him even more. But do we know him any better?

✒ The Year of Magical Thinking, by Joan Didion (HarperCollins)

Devastating personal account by America's classiest non-fiction writer of her attempt to come to terms with the sudden death of her husband and the fatal illness of her only daughter.

✒ Postwar, by Tony Judt (Pimlico)

The first vivid, detailed study of the continent's post-1945 recovery to take in all of Europe, east and west.

✒ Saturday, by Ian McEwan (Vintage)

The march against the war in Iraq, a cameo for Tony Blair in Tate Modern and a lovingly assembled fish stew – the novel that summed up New Labour.

2006

Christopher Hitchens on The God Delusion, by Richard Dawkins (Black Swan)

There are numberless reasons for regarding The God Delusion as a modern classic and one of these reasons, I would propose, is its relative superfluity. Richard Dawkins has already introduced millions of people to the rigour and beauty of the scientific worldview and shown in exquisite detail the ways in which we, like all our fellow creatures, have evolved and were in no meaningful sense "created".

Before the arid term "scientist" was coined in the last century, men such as Newton and Darwin were reckoned as "natural philosophers": a term that suits Dawkins very well. Another scholar deserving of the same title of honour was the late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, and The God Delusion can be read as a response to Gould's conciliatory and wishful proposition that "science" and "faith" (or religion) occupy "non-overlapping magisteria".

Dawkins's energy, industry and wit, in disputing this idle view and in showing the hard, historic incompatibilities between the two, have led to his being caricatured as a dogmatist in his own right, even as a "fundamentalist". What empty piffle this is. A senior teacher in the vital field of biology finds his discipline under the crudest form of attack, and sees government money being squandered on the teaching of drivel in schools. What sort of tutor would he be if he did not rise to the defence of his own profession? Thus the appearance of a secondary work that ought not to have been needed at all, but is in fact required now more than ever.

The God Delusion is, like Daniel Dennett's Breaking the Spell, quite respectful of the human origins of religion and of the ways in which it may have assisted people in spiritual and even material ways. We are pattern-seeking primates, and religion was our first attempt to make sense of nature and the cosmos. This does not give us permission, however, to go on pretending that religion is other than man-made. And the worst excuse ever invented for the exertion of power by one primate over another is the claim that certain primates have God on their side. It is not only justifiable to be impatient and contemptuous when such tyrannies are proposed; it's more like a duty.

The atheist does not say and cannot prove that there is no deity. He or she says that no persuasive evidence or argument has ever been adduced for the notion. Surely this should place the burden on the faithful, who do after all make very large claims for themselves and their religions. But not a bit of it: we are somehow supposed to regard the profession of "faith" as if it were a good thing in itself. This is too much to ask, and it was high time to say so.

I regret to say that I have just noticed a tiny mistake on page 177. It is not true to say that the Virgin Mary "ascended" into heaven. She was "assumed" into that place, by a ruling of the Roman Catholic church that dates back all the way to the mid-19th century. Dawkins really must be more careful, but he may have been busy, as in the chapter of Climbing Mount Improbable in which he described the 20 or so separate evolutions of the eye. Readers of The God Delusion ought to press on and buy all the other Dawkins volumes too. •

✒ The Road, by Cormac McCarthy (Picador)

The novel that crystallised our era's fears of environmental apocalypse – and may just terrify us into action.

✒ The Looming Tower, by Lawrence Wright (Penguin)

Pulitzer-prizewinning investigation into the origins of al-Qaida and the runup to 9/11.

✒ The Weather Makers, by Tim Flannery (Penguin)

Acclaimed, influential study of the dire consequences of global warming, and possible solutions.

✒ The Revenge of Gaia, by James Lovelock (Penguin)

No longer a prophet in the wilderness, Lovelock and his theory of a living planet are now cornerstones of the environmental debate.

2007

Alison Lurie on Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, by JK Rowling (Bloomsbury)

Why are these books such a worldwide phenomenon? Yes, they are very good, but many equally good books have appeared without causing near-riots on publication day. The best explanation I can come up with is that, like the popular dramas of Shakespeare's time, they excel in many genres simultaneously. As Polonius puts it when recommending the company of travelling actors that visits Elsinore, they are outstanding "either for tragedy, comedy, history, pastoral, pastoral-comical, historical-pastoral, tragical-historical, [or] tragical-comical-historical-pastoral". Something for everyone, all of it first-rate.

The Harry Potter books can be enjoyed by readers who like jokes and puns and original, often outsize comic characters such as Hagrid. At the same time, they are exciting tales of adventure, mystery and detection. And they are also classic boarding-school stories, full of admirable and hateful teachers, thrilling sports competitions, midnight feasts, loyal friendships and bitter rivalries between houses. They are fantasies, too, and like Shakespeare contain witches, wizards, elves, ghosts, spells and transformations. They also have affinities with speculative fiction, being full of original supernatural inventions and devices. All this gives pleasure to many kinds of readers. But the books are serious, too; in them good people as well as bad ones die, giving their lives for the sake of a greater cause, like many heroes of Elizabethan drama. Some of the most admirable adult characters, as in Shakespeare, are also revealed to have a tragic flaw that causes them to hesitate to act, to make foolish errors of judgment, to lie, or even to commit murder.

As in the best juvenile fiction, the novels' young heroes are not perfect beings. Harry is good at Quidditch, but his eyesight is poor, he is only an average student, and his unhappy childhood has made him something of a loner. Hermione is intellectually brilliant, but also opinionated, bossy and a grind. Ron is loyal and brave, but sometimes clueless. Had it not been for the necessities of plot, the Sorting Hat would surely have made him a Hufflepuff and Hermione a Ravensclaw.

Moreover, though the prevailing style of Rowling's books is lively and upbeat, there are darker undertones. As the author put it in a recent interview: "My books are largely about death. They open with the deaths of Harry's parents. There is Voldemort's obsession with conquering death and his quest for immortality at any price." Even in this magical world it is a quest in which none can succeed. Evil, too, is never totally defeated. In the epilogue at the end of the series, 19 years later, there is still a Slytherin House at Hogwarts, and some of the students boarding the train at platform 9¾ are bound for it. •

✒ The Suspicions of Mr Whicher, by Kate Summerscale (Bloomsbury)

More genre-blurring: this social history reads like a murder mystery and deserved its enormous success.

✒ The Blair Years: Extracts from the Alastair Campbell Diaries (Arrow)

Compelling portrait of power in action from an irascible insider.

✒ Half of a Yellow Sun, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Harper Perennial)

The first great African novel of the new century, detailing the horrors of the Nigerian civil war.

✒ The Reluctant Fundamentalist, by Mohsin Hamid (Penguin)

A spare, unsettling portrayal of the uneasy relationship between east and west as a Pakistani Muslim relates his experiences of living in post-9/11 New York.

2008

Lorrie Moore on Change We Can Believe In, The Audacity of Hope and Dreams from My Father, by Barack Obama (Canongate)

In 2008 Obama's new book was Change We Can Believe In, but for most of the reading public all of his books were new, and his early memoir, reissued, had begun to be read widely that same year. Unlike Change We Can Believe In and The Audacity of Hope, Dreams from My Father was not about policy. It was written before the politician who wrote the others had even been hatched (hatched as a plan rather than as a creature). Dreams from My Father contains Obama's most spellbinding writing. It was the book most Americans were talking about in 2008. Within its pages is a vulnerable portrait of the boy who became the man; resilience is its theme. First published in 1995 when Obama was 33 and selling very few copies (the bulk of its first printing was pulped), a signed first edition now sells for five figures or sometimes six. For those of you who missed out on this deal, get in line, and we will pool our dimes for a cheap hypnotist who will rid all financial regret from our minds so that we can concentrate on what is more important – or at least more literary.

Dreams from My Father is surely (ironically, via its partially telescoped pacing and its storytelling licence generally) one of the truest glimpses into Obama the young man and boy. Written when he wanted to be a writer (rather than when he was contemplating the burdens of being commander-in-chief) and when he was thinking of readers rather than voters, it offers a candour and vividness one will not see in a more ordinary political memoir. There is sex, there is drugs, but they are completely unsensational. He is matter-of-fact and unself-pitying even as self-pity is a thematic corollary to his subject of identity.

Dreams from My Father is less about idealism than about boulders in the road: does one smash them, rope and haul them, go around them? Napping or retreating aren't options. What Obama offers is an intriguing portrait of family restlessness, which afflicted both his parents and his grandfathers as well as Obama himself – a restlessness that caused him not to shy from challenges but to use boredom and frustration and good intentions to step up and over them. In Dreams from My Father, family yarns are unspooled and analysed, as if they were indeed dreams, with a dream's strange fleeings, chases and believable changes. One of the most memorable is of his four-year-old Kenyan father running away with his older sister, who was running away to find their mother, who had also run away; it is a heart-stopping tale of African village life. Equally stunning is the stoical story of the Indonesian stepfather who attempted to toughen the young Barack by boxing him in the face. If one is wondering who this new leader of the western world really is, Dreams from My Father addresses it best. •

✒ The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century, by Alex Ross (Harper Perennial)

Contemporary classical music found its voice in the age of the blog.

✒ Netherland, by Joseph O'Neill (Harper Perennial)

Cricket, gangsters and mid-life crisis in post-9/11 New York.

✒ The Forever War, by Dexter Filkins (Vintage)

Hardhitting dispatches from the frontline in Iraq and Afghanistan that have already achieved classic status.

✒ Home, by Marilynne Robinson (Virago)

Proved it's still possible to write a best-selling novel about religious doubt. Winner of the Orange prize.

✒ The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science, by Richard Holmes (Harper Press)

Cultural history of science that delighted both lay readers and the scientific establishment.

2009

John Mullan on Wolf Hall, by Hilary Mantel (Fourth Estate)

As Booker judges this year, we found ourselves shortlisting six historical novels. Yet suggestions of quaintness and self-consciousness remained attached to the genre. Not now. With Wolf Hall, the richly deserving winner, Mantel redeemed historical fiction from archaism and undigestible "research". Intensely pleasurable, it is also a work of technical audacity. It is told in the third person, but entirely through the thoughts of Thomas Cromwell, a courtier who acquires power in ways that sometimes surprise even himself. Mantel makes him her accomplice in the art of noticing things, the precious points of light in a darkened world – "the flashes of fire from Wolsey's turquoise ring", "the spinning of sparkling dust in empty rooms" – and the small gestures by which men and women give themselves away.

It is a big book, but to get at its brilliance you need to isolate passages, even sentences. In one typical sequence of paragraphs, we observe with Cromwell the attempts of his kitchen boys to make spiced wafers on hot irons, while he muses on his attempts to manipulate rancorous politicians and restrain Anne Boleyn's status-hungry father. Domestic detail and political manoeuvre are interleaved, as the protagonist watches one thing and thinks of another. It is learnt from the stream-of-consciousness narrative of Virginia Woolf and her imitators, but it is also something sharp and idiosyncratic. Cromwell's mind does not flit from one thought to another: it tirelessly works to separate experience into its categories, to make the chaos of human needs intelligible.

The novel makes Cromwell its hero and Sir Thomas More its villain. Cromwell is a tolerant, enlightened servant of power, who attempts to limit the violence it can do. More is a chilly fanatic, bent on achieving religious rectitude by torture and terror. You can understand the suspicions of some historians, for, on this showing, Mantel could persuasively rewrite history in any way she fancied. Yet she also allows the reader to see this – to know on every page that we are exercising our imaginations.

When she wants us to see something, we do. The novel's representations of violence are extraordinary. In one episode that you would like to forget but cannot, an old woman – an obdurate Protestant – is burnt at the stake. Writers and film-makers have often enough reimagined for us what this terrible exhibition would have been like, but never as here. It is made real because it is percolated through Cromwell's mind as he recalls the spectacle from his boyhood: "They had said it would not take long, but it did take long."

This year many novels adopted the present historic tense, as Wolf Hall does. In most cases, the technique flourishes its literariness. Here it seems just and inevitable. There is no vantage point beyond the unfolding of events. Mantel's protagonist is a man of restive intelligence, but not able to see beyond this here, this now. We experience his here and now with him. We think we "know" this history, but we un-know it again as we read this novel. •

✒ 2666, by Roberto Bolaño (Picador)

Novel in parts from the decade's biggest fiction discovery, which combines literary playfulness with visceral reports of the murders in Ciudad Juárez.

✒ Brooklyn, by Colm Tóibín (Viking)

Elegant, heartbreaking novel about Irish girl who emigrates to New York in the 1950s.

The best of the rest written by the Review team.

Monday, December 7, 2009

What we were reading

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment