- From , January 3, 2010

In a packed Istanbul courtroom in December 2005, Orhan Pamuk, Turkey’s most acclaimed writer, faced trial and imprisonment for “insulting Turkishness”. Provoked by comments he’d made about mass killings of Armenians and Kurds in Turkey, the charge (eventually dropped) could hardly have been more misdirected. For, as his new novel again testifies, what suffuses his books and gives them their distinctive appeal is keen empathy with Turkey and its ways of life.Susceptibility to international literary influences can overload Pamuk’s fiction with emulations of Kafka, Borges, Nabokov and the like, and clutter his work with the apparatus of bygone experimentalism. But the instant he pulls free of this and writes —vividly, feelingly and illuminatingly — about Turkey’s unsettled present and the resplendent past from which it has emerged, his pages leap to life.

Istanbul (2005), his fine commemoration of the city in which he has lived for more than half a century, poignantly evokes the post-imperial melancholy hanging over the metropolis on the Bosphorus and its crumbling reminders of Byzantine and Ottoman supremacy. His 2001 novel, My Name Is Red, an intricate murder tale set in 16th-century Istanbul, brilliantly portrayed Ottoman miniaturists in their studios shaken by the impact of Renaissance Italian perspectives on their religiously orthodox procedures. The culture clash in his last novel, Snow (2004), was between contemporary secularism and Islamist militancy in a Turkish border city where wearing the headscarf has become a flag of defiance. Headscarves also feature in The Museum of Innocence. But, with the period moving back to the 1970s and the setting once again Istanbul, they are viewed by most characters here as the sad garb of female dowdies from the provinces.

The son of a wealthy westernised family, Kemal (whose story the book recounts) is spruce with sophisticated gloss and, when the novel opens, about to be engaged to Sibel, also from Istanbul’s cosmopolitan high society. Congratulating themselves on their liberated lifestyle and emancipation frompuritanical taboos, they have discreetly become lovers before marriage.

But unknown to Sibel, and even more surreptitiously, Kemal has recently acquired another lover: Fusun, an attractive young shopgirl. Short chapters flicker between Sibel and Kemal in chic venues such as the Pera Palas hotel or modish French-style restaurants, and Fusun and Kemal in lowlier surroundings. Then the novel opens up into a tour-de-force portrayal of his engagement party at the Hilton, awash with black-market whisky and champagne and thronged with Istanbul’s rich bourgeoisie, sleekly jostling to seem impeccably westernised. Sharply observant but registering the warm gregariousness as well as the social showiness of the guests, this terrifically rendered episode, swirling with characters and incident, marks the novel’s turning-point, during which Kemal resolves to commit himself to Fusun, not Sibel. Disappointingly, it is also its high spot, after which things become increasingly anticlimactic.

When Fusun disappears after the party, Kemal spends “339 days of agony” desperately searching for her. Expatiations on memory, jealousy, obsession and possession underline the way this section of the book closely replicates Proust’s account of the search for a runaway girlfriend in Albertine Disparue. And as always when Pamuk imitates one of his literary idols, the novel's vitality droops.

Fusun’s return doesn’t relieve the listlessness. Aiming to exhibit the enduring strengths of traditional if impoverished Turkish domestic life, Pamuk has Kemal improbably courting her for “seven years and 10 months” at her parents’ house. Here, as Istanbul struggles through its “terror years” of political assassinations, bombings, shootings, street battles between left and right, curfews and military coups, he has supper with the family “1,593 times” and relishes their uneventful evenings of trite chat while watching television. The humdrum routines surrounding his chaste wooing of Fusun gradually extend into his compulsive collecting of items associated with her (including 4,213 of her cigarette butts). In a venture weirdly paralleling Pamuk’s recent real-life setting up of a museum of everyday Turkish life, he ultimately gathers all this into a museum in her honour.

As a study of obsessive sexual and emotional attachment, the novel fails to grip. Where it does exert a hold is in its enthralment with Istanbul. Atmospheric vignettes of the city (from mouldering Ottoman mansions on the waterfront tocobbled backstreets winding past graffiti-daubed broken marble fountains and mosques amid ancient mulberry trees) coexist with fascinating insights into a society tugged between East and West. This novel, the first Pamuk has published since he won the Nobel prize for literature in 2006, isn’t the most outstanding of his bulletins from the Bosphorus. But, at its best, it adds another engrossing dimension to his continuing fictional exploration, documentation and celebration of Turkishness.

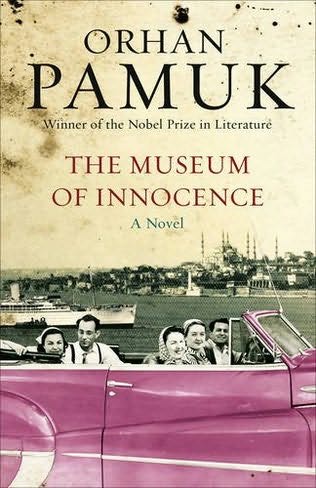

The Museum of Innocence by Orhan Pamuk, translated by Maureen Freely

Faber £18.99 pp536

Monday, January 11, 2010

The Museum of Innocence by Orham Pamuk

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment